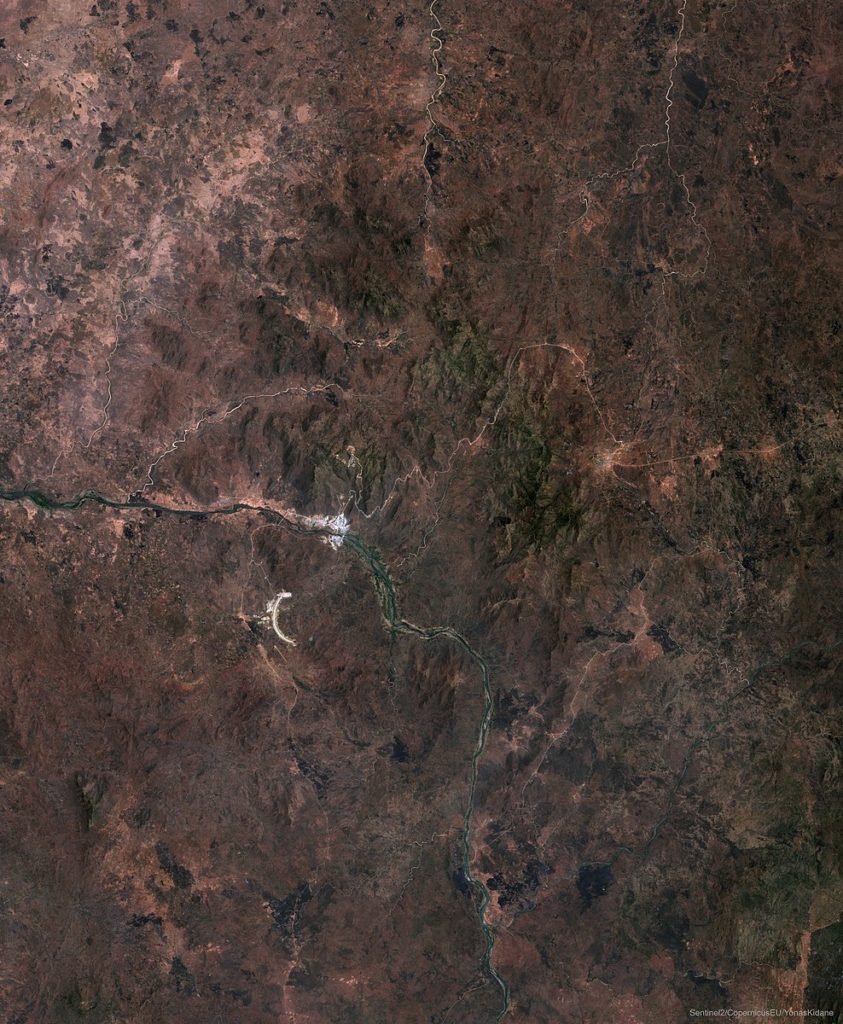

Crises are beginning to accumulate in Ethiopia. It is only a matter of time before one explodes in a significant regional and perhaps global catastrophe. While prior posts have looked at the country’s growing threat of civil war, a less discussed crisis is the GERD or Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam.

The GERD is a massive hydropower dam built on the waters of the Blue Nile in Ethiopia. Construction of the GERD began in 2011 and with an expected completion date in the next year. It is part of Ethiopia’s strategy to become one of the world’s leading exporters of electrical power. Once it becomes fully operational, Ethiopian leaders expect the GERD to transform life in their country by supplying 65 million people there with electricity powered by the dam. The GERD will be the largest dam on the continent of Africa and the 7th largest in the world. Neighboring countries in the Horn of Africa expect to also benefit from the electrical power produced by the GERD.

The problem is that what takes place with the water of the Nile River Basin in Ethiopia does not affect Ethiopia aloe. The Nile River Basin flows north through 11 countries on the African continent. Egypt is among the world’s fastest-growing countries, and its 100 million population relies on the waters of the Nile for 90% of the country’s freshwater needs. Egypt is already short of water. The country imports half of its food needs, and Egypt recycles 25 billion cubic meters of water every year.

The waters of the Blue and White Niles converge north of Ethiopia in Sudan and flow north to Egypt from there. In 1959 Egypt and Sudan signed a set of agreements that determined how they would break down the waters of the Nile. Egypt got a significantly larger portion than Sudan. No other nations were included in those discussions or decisions more than half a century ago. Today, restrictions of the Nile waters could mean catastrophe for Egypt, while a continuation of the 1959 agreements, regardless of rainfall shortages, could mean failure for the GERD.

In July, Egypt accused Ethiopia of violating international law after Egypt and Sudan received notice that the dam was filling up with water and limiting the flow of the Nile waters to Egypt. This is the second year in a row that Ethiopia filled its reservoirs using the GERD despite protests from Egypt and Sudan.

Although negotiations between Egypt and Ethiopia have been ongoing for a decade, those negotiations collapsed earlier this spring. Egypt and Sudan have asked the United Nations to discuss the issue, but currently, the UN is more focused on the Tigray Crisis.

As the water crises intensify in different parts of the planet, the legitimate threat of resource wars is no longer something far off on the horizon. The debate over the GERD could serve as the perfect basis for spreading Ethiopia’s already dire Tigray Crisis into a wider regional war.