In the 1990s, stories of genocide and ethnic cleansing in the Balkans rocked the western world. Commentators described the events as the worst mass murders in Europe since the holocaust. Osama bin Laden himself cited the atrocities of Christian Serbs against Bosnian Muslims as one piece of justification for his war against the west. More than 100,000 died in the fighting, and another 1.2 million were classified as internally displaced. The story of the 1990’s violence reaches back further than the fall of Communism, and nationalism acted as a critical ingredient to the fires that raged there.

Serbian Nationalism

Many Serbs mark the beginning of Serbian nationalism to a long-forgotten Battle of Kosovo in 1389 between Serbia and the invading Ottoman Empire. Most scholars mark the early 19th century, when Serbs began to rise against the waning Ottoman Empire, which they were part of, as the origin for Serb nationalism.

During this period of the 19th century, activists defined Serbs as a group in the Balkans that shared a common language and dialect. They promoted the idea of Greater Serbia as a nation that would host all Serbians in the Balkans. Under the concept of Greater Serbia, all territory historically held by the Serbians would be united under Serbian rule and independent of outside powers and rulers.

Independence and Defeating the Ottomans

The decline of the Ottoman Empire was expedited throughout the 19th century by a series of wars fought with Russia. During that time, Serbian nationalists secured some measure of independence from the Ottomans. In 1878, after the last of the 19th-century wars between Russia and the Ottomans, Serbia was recognized as an independent state.

The new Serbian government still saw their quest for independence as incomplete. The Serbian leaders believed the Austro-Hungarian Empire still occupied lands and people that rightfully belonged to their historical vision of a Greater Serbia. In 1908 Austria annexed Bosnia and its sizeable Serbian population, which greatly offended those who held the vision of Serbian nationalism.

In 1912 Serbia joined the Balkan League, which included Greece, Bulgaria, and Montenegro, in a war against the Ottomans that finally removed the Ottomans from nearly the entire Balkan region of Europe. Now the remaining opponent to Serbian nationalism in Europe was Austria. Russia promised its military support to Serbia in Serbia’s contest for independence and nationalism against the Austrians.

These agreements and ambitions set the stage for the events that launched World War I.

World War I

On June 28, 1914, a nineteen-year-old Serbian nationalist assassinated the Crown Prince of Austria, Franz Ferdinand, while Ferdinand visited the Bosnian capital city Sarajevo. The assassination exploded into a sequence of unintended consequences and unleashed the horrors of World War I.

Serbia suffered the highest casualty rate of World War I. Among Serbia’s population of 4.6 million, more than 25% became casualties of the war, including 58% of the male population. Austria occupied Serbia and took control of the capital city of Belgrade.

Despite the pain of World War I, among Serbian nationalists, the gains of World War I deemed that hefty sacrifice worthwhile. By the end of the Great War, the historical enemies to Greater Serbia fell defeated, and the pathway toward Serbian nationalism appeared unimpeded.

The Birth of Yugoslavia

The aims of Serbian nationalism were achieved but in an unexpected format. Rather than an independent state for Serbia, the designers of the modern world at the Paris Peace Conference after World War I opted for the appeal of an independent state for the Slavic peoples of Southern Europe.

The word Yugoslavia derives from the Slavic words for South Slavs. The idea of Yugoslavia competed throughout the 19th century with appeals for nationalism by the Serbs, Croats, Bosniaks, Albanians, and Slovene nationalists.

At the Paris Peace Conference, the designers of Yugoslavia saw the difference in these Slavic people groups as relatively minor. From a shared language perspective, it was the difference between American and British English. From a religious history perspective, many adhered to Eastern Orthodox Christianity while others adhered to Catholicism. A small minority still adhered to Islam in Bosnia and Hercegovina. From the perception of the post-war planners, the benefits of Yugoslavia outweighed the potential detriments.

Yugoslavia gained international recognition on July 13, 1922, and its first ruler was the Serb Peter I.

Although the idea of Yugoslavia made sense to the planners at the Paris Peace Conference, many nationalists became increasingly offended by the idea. They felt their dreams of self-determination derailed by the invention of Yugoslavia.

Internal Divisions

Serbian politicians operating within the government of Yugoslavia worked to keep Croats in a minority status politically. For these nationalists, Yugoslavia became the new version of Greater Serbia.

Croat, Slovene, and Macedonian nationalist groups resisted the influence of Serbian nationalism in Yugoslavia. Various terrorist organizations arose in the first decades after Yugoslavia’s establishment. The rise of extremism from these nationalist groups triggered Serbian nationalism to inflame even more.

In 1928 a Serbian politician opened fire in Yugoslavia’s parliament, killing three members of the Croatian party. The King of Yugoslavia, a Serbian, used the crisis to ban political parties to reduce separatist ideologies within the country. In 1932 a Macedonian nationalist assassinated the king.

By the end of the 1930s, Yugoslavia appeared to be heading toward division between Croats and Serbians. That direction was subverted, however, when the Axis powers invaded in 1941. Yugoslavia was dismembered, and the plans of the Paris Peace Conference made after World War I were erased.

World War II Ethnic Cleansing

After 11 days of resistance to the Axis powers, the various regions of Yugoslavia signed an armistice with Germany. More than 300,000 Yugoslavian officers were taken prisoner. Germany established an independent state of Croatia, essentially a satellite Nazi state ruled by a fascist militia group known as the Ustase.

Between 1941 and 1945, the Ustase carried out mass killings and crimes against humanity within the borders of the Independent State of Croatia. More than half a million Jews, Serbs, and gypsies were killed. Another 250,000 were expelled from the country. The Ustase implemented forced conversions to Catholicism throughout Croatia. The Ustase, mimicking their Nazi overlords, wished to design a pure Croatian society.

While the Ustase sought to eradicate the Jews and gypsies from their land, they planned to merely neutralize the Serbs. According to the Croat strategy, one-third of the Serbs should be killed, one-third deported, and one-third converted to Catholicism. The Ustase believed this strategy would render the Serbs politically harmless to a pure Croatia.

Meanwhile, a Serbian nationalist group known as the Chetniks refused to surrender to the Germans and began campaigns of guerilla activity against the Ustase. The Chetniks viewed non-Serbian residents of Yugoslavia as “traitors” and started a campaign of ethnic cleansing against Muslims and Croats. Members of the Chetniks wrote of “cleansing the land of all non-Serb elements.” The Chetniks believed and promoted the idea that all Muslims and Croats were accomplices to the crimes of the Ustase.

In 1941 the Chetniks initiated a series of massacres against Croats and Muslims throughout Yugoslavia. In many instances, the Chetniks also targeted Jews and Albanians. They razed mosques and Catholic churches. The Chetniks wiped out entire villages. The exact death counts by Chetnik ethnic cleansing are debated but range from 50,000 to 500,000 among scholars.

Many other Serbs followed the partisan leader, Josip Broz Tito, a Croat. After the war, thousands of Chetniks fled to neighboring countries. The Allies returned to Chetniks to Yugoslavia. From 1945-46 Tito’s forces killed tens of thousands of former Chetniks and other political opponents.

An estimated 10.8% of Yugoslavia’s population perished in World War II before the expulsion of the Germans in 1944. In 1945 Yugoslavia fell under Soviet control.

Communist Rule

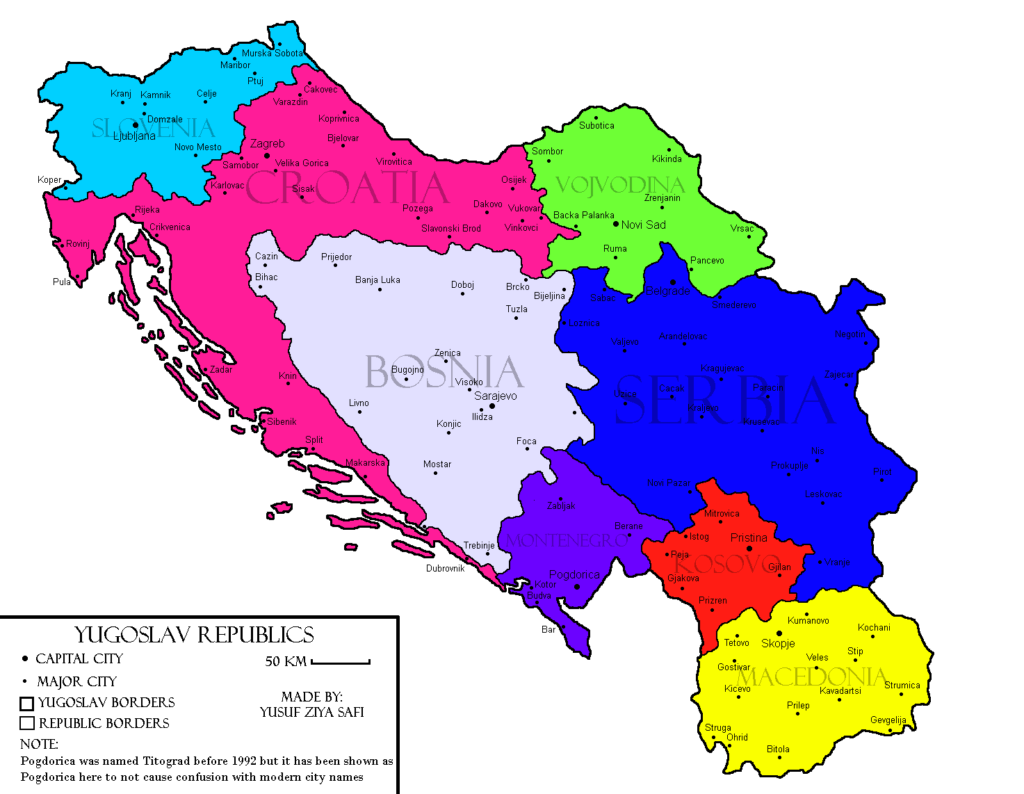

In 1946 a new national constitution, modeled after the Soviet Union, was ratified and the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia declared. The new Yugoslavia consisted of six republics: Serbia, Bosnia and Hercegovina, Croatia, Slovenia, Montenegro, and Macedonia, as well as two autonomous regions Kosovo and Vojvodina. Tito became the new president of Yugoslavia. Tito held that role until he died in 1980. The resentment felt between the different nationalist groups was buried for a while but never completely vanished.

Josip Broz Tito – President of the SFR Yugoslavia, 1945-1980.

After Tito’s death, the rulership of Yugoslavia rotated annually between the six republics of the federation. This process reduced central authority in the government and accelerated the restoration of divisions between the republics.

The Return of Nationalism

As Yugoslavia splintered throughout the 1980s, a resurgence of Serbian nationalism filled the vacuum. Serbian academics and politicians inflamed these divisions. In the mid-1980s, a group of Serbian nationalist academics declared that the Serbs were in danger of genocide at the hands of the Albanians in Kosovo.

Slobodan Milosevic, leader of the League of Serbian Communists, took over the cause of Serbian nationalism for his political gains. After clashes between Serbian nationalists and police in Kosovo, Milosevic declared to the nationalists, “No one should dare to beat you!” Milosevic’s declaration became a rallying cry for Serb nationalists.

In 1989 Milosevic initiated a repressive drive in Kosovo where tens of thousands of Kosovars (ethnic Albanians) were dismissed from their jobs. This was the event that triggered the full unraveling of Yugoslavia. Kosovo turned into a primarily militarized area for the Serbs, and events in the Balkans began their dark turn.

The Balkan Wars

Between 1991 and 1992, Yugoslavia exploded into open war. Croatia and Slovenia declared their independence. The sizable population of Serbs living within Croatia likewise proclaimed their independence. Milosevic began calling Serbs toward the vision of Greater Serbia once again, giving him the ideology and justification for the fighting that was about to occur. In 1992 Bosnia and Hercegovina declared

Reports of ethnic cleansing began to emerge out of the Balkans. Two hundred wounded Croatian soldiers were massacred in their hospital beds. Bosnia became the most brutal front of the war. The Serbs laid siege to the capital city of Sarajevo. Muslim landmarks and cultural histories in Bosnia were burned to the ground. In other parts of the country, Bosnians found themselves fighting Serbs and Croats, although the Serbs carried out most of the war crimes. The Serbs established concentration camps to house Bosnians, where torture and extreme conditions led to the deaths of hundreds of Bosnian Muslims.

By 1992 reports of mass executions and widespread rape led to outrage around the world. Convinced that Serbians and Bosnians could never live together in peace, a strategy of ethnic cleansing was now in place. The Serbian military would surround Bosnian populated areas, execute the leaders and intellectuals, then begin separating the men from the women. While the Serbs executed the men, the women were transported to locations outside of Greater Serbia. Frequently the women became subject to brutal sexual violence. The term genocidal rape became common in subsequent studies of the atrocities in Bosnia.

Srebrenica represented the pinnacle of the violence where Serbs killed more than 8,000 men and boys. Srebrenica was one of several cities defined as a safe zone by the United Nations. Many Muslim refugees took shelter in Srebrenica only to find the United Nations’ military units ill-equipped to protect the city adequately.

Kosovo

The Serbs established a police state over Kosovo beginning in 1989. An armed guerilla movement eventually developed made up of Kosovar Albanians fed up with the apartheid system enforced upon them. As the guerilla violence intensified beginning in 1998, the Serbians intensified violence against the ethnic Albanian civilians. More than 200,000 Albanians were displaced. A massive campaign of ethnic cleansing followed where the Serbs sought to push Albanians over the border into Macedonia and Albania.

In the spring of 1999, NATO launched high-altitude bombings on Serb positions in Kosovo. The bombing only inflamed the Serbian activity against the Albanians. The Serbs expelled around 800,000 Kosovar across the borders, killing ten thousand in the process.

As NATO and UN forces slowly arrived in Kosovo to finally stop the violence, Albanians launched revenge attacks against Serbian civilians in northern Kosovo.

The End of Milosevic

A drawn out peace process eventually ended the fighting in the Balkans. Milosevic was arrested for war crimes but died in 2006 while still on trial.