Venezuela’s oil industry: A history of abundance, ambition, and adversity

Venezuela’s oil industry has long been the backbone of its economy and a defining force in its global identity. With the largest proven oil reserves in the world—estimated at over 303 billion barrels—Venezuela’s petroleum wealth has shaped its political, economic, and social trajectory for more than a century. Yet, this immense resource has also exposed the country to volatility, mismanagement, and geopolitical tension.

Origins and Early Development

Oil seepages were known to Venezuela’s Indigenous peoples long before colonization. They used the thick black substance, known as mene, for medicinal and waterproofing purposes. The first documented shipment of Venezuelan oil occurred in 1539, when a barrel was sent to Spain to treat Emperor Charles V’s gout.

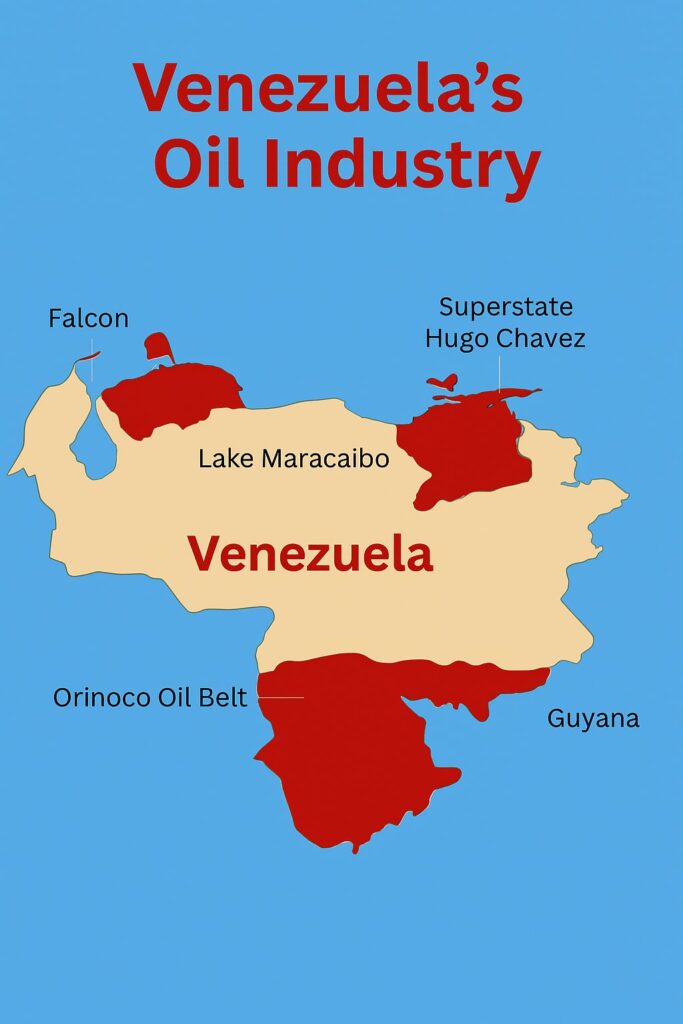

The modern oil era began in 1914, when the Zumaque I well struck oil in the Maracaibo Basin. This discovery marked the birth of Venezuela’s commercial oil industry. Foreign companies, especially from the U.S. and Europe, rushed in. By the 1930s, foreign firms controlled 98% of Venezuela’s oil output, with Standard Oil and Royal Dutch Shell dominating the landscape.

Nationalization and PDVSA

In 1976, Venezuela nationalized its oil industry, creating Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA). This move was part of a broader wave of resource nationalism across Latin America. PDVSA became one of the most respected state-run oil companies globally, known for its technical expertise and efficiency.

During the oil boom of the 1970s, Venezuela was dubbed “Saudi Venezuela.” Petrodollars funded infrastructure, education, and social programs. However, the economy became dangerously dependent on oil, which accounted for over 90% of export revenues.

Decline and Mismanagement

The 1980s oil price crash exposed Venezuela’s vulnerability. Debt soared, inflation surged, and poverty deepened. In response, the government imposed austerity measures, triggering the 1989 El Caracazo uprising—a violent protest that marked a turning point in public trust.

Hugo Chávez rose to power in 1998, promising a “Bolivarian Revolution” funded by oil wealth. Initially, poverty declined and social spending increased. But Chávez’s policies—mass nationalizations, strict currency controls, and politicization of PDVSA—undermined the industry’s efficiency. By 2011, oil made up 96% of Venezuela’s exports, leaving the economy exposed to global price swings.

Strengths of Venezuela’s Oil Industry

- Massive reserves: Venezuela holds the world’s largest proven oil reserves, surpassing Saudi Arabia and Iran.

- Strategic location: Proximity to the U.S. Gulf Coast refineries made Venezuela a key supplier for decades.

- Experienced workforce: PDVSA once boasted a highly skilled technical staff and global partnerships.

Weaknesses and Challenges

- Heavy crude: Much of Venezuela’s oil is extra-heavy and located in the Orinoco Belt. It requires costly refining and blending with lighter crude to be commercially viable.

- Infrastructure decay: Years of underinvestment and mismanagement have crippled pipelines, refineries, and export terminals.

- Political interference: PDVSA became a political tool under Chávez and Maduro, leading to brain drain and corruption.

- Sanctions and isolation: U.S. and international sanctions have restricted Venezuela’s access to markets, technology, and capital.

Geopolitical Impact

Venezuela’s oil wealth has made it a focal point in global politics. During the Cold War, the U.S. supported anti-communist regimes to protect oil interests. In recent years, sanctions and diplomatic isolation have pushed Venezuela toward alliances with Russia, China, and Iran, reshaping hemispheric dynamics.

What the Future Holds

Venezuela’s oil industry remains a paradox: immense potential trapped by dysfunction. Reviving the sector would require:

- Depoliticizing PDVSA and restoring technical expertise

- Attracting foreign investment and modernizing infrastructure

- Diversifying the economy to reduce oil dependency

Until then, Venezuela’s oil wealth will continue to be both a blessing and a burden—an untapped promise waiting for reform.