For five centuries, the Great Powers of the world—Spain, Britain, France, the United States, Russia, Japan, and others—pursued imperialism with the same conviction that gravity pulls downward. Empire was not merely a policy; it was a worldview, a presumption of destiny. Yet history has delivered its verdict with cold consistency: imperialism always fails. It fails morally, strategically, economically, and ultimately existentially. And the lessons, written in the blood and ruins of conquered peoples, have been astonishingly slow for empires to learn.

Today, as new forms of expansionism reappear on the world stage, the seven hard lessons of imperialism deserve renewed attention—not as abstractions, but as lived realities measured in human lives. These are the lessons that should have been considered before the US pursued regime change in Venezuela this past weekend. The kidnapping of the dictator Nicolás Maduro—fits a long pattern of U.S. imperialism in Latin America, but rarely have those efforts been so public and brazen.

Critics contend that by supporting covert operations, backing opposition factions, and attempting to remove a foreign leader through extrajudicial means, Trump extended a century-old tradition of U.S. intervention designed to shape political outcomes in the region. According to this view, the United States has repeatedly used economic pressure, sanctions, and covert action to influence governments it considers hostile to its interests. In the case of Venezuela, critics say Trump framed the operation as a fight for democracy while simultaneously asserting U.S. dominance over another nation’s sovereignty.

Forcibly extracting or overthrowing a sitting head of state—regardless of that leader’s legitimacy—reflects an imperial mindset that treats Latin American nations as arenas for American power rather than independent countries with the right to self-determination. The policymakers who supported such a move would do well to recall the seven hard lessons the greater powers learned about imperialism before America took these first steps into what is sure to become a quagmire.

-

Imperialism Always Breeds Atrocity

Empires rarely admit this, but the historical record is unambiguous: imperialism and atrocity are inseparable. The logic of empire—domination, extraction, racial hierarchy—creates the conditions for mass violence long before the first shot is fired.

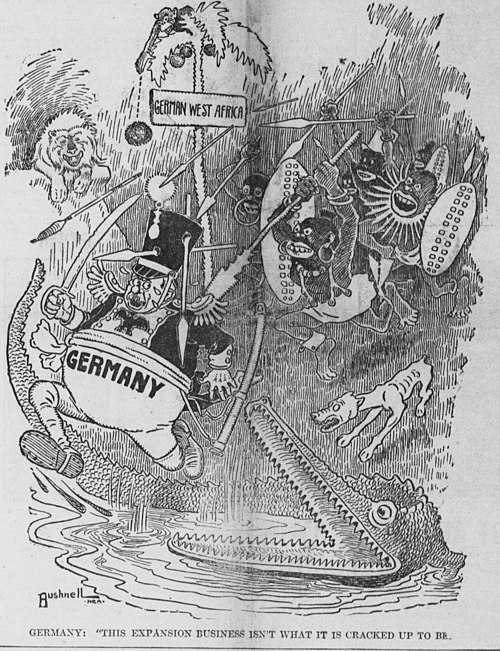

Genocide scholars have increasingly emphasized the deep link between imperial expansion and mass killing, noting that Western empires committed or enabled genocides across the 19th and 20th centuries. The French conquest of Algeria, the German extermination of the Herero and Nama in Namibia, the Belgian terror in the Congo, and the American conquest of the Philippines all share the same pattern: when a people resists domination, the empire escalates to annihilation.

Consider the Philippine-American War (1899–1902), a conflict that has largely slipped into what one historian calls “a memory hole.” American forces, determined to seize control of the islands after Spain’s defeat, waged a brutal counterinsurgency campaign. Torture was widespread. Prisoners were executed. Entire villages were burned. Civilians were herded into concentration camps where disease and starvation killed thousands. Estimates vary, but scholars place Filipino civilian deaths in the hundreds of thousands—an astonishing toll for a war that most Americans barely remember.

The lesson is stark: imperialism is not merely accompanied by atrocity; imperialism requires it!

-

Empires Misjudge the Costs—Every Time

Imperialism is always sold as a bargain. The British believed India would pay for itself. The French believed Algeria would become a profitable extension of the metropole. The Americans believed the Philippines would be a stepping stone to Asian markets. But the arithmetic of empire is a fantasy.

The United States, for example, lost 4,200 soldiers in the Philippine War and spent the equivalent of billions of dollars in today’s currency to suppress a population that had already declared its independence. Britain spent more on garrisoning India than it ever extracted in revenue. France poured treasure and lives into Algeria for 132 years, only to lose it in a catastrophic war that nearly toppled the Fifth Republic.

Imperialism is a fiscal black hole. The costs balloon and the benefits evaporate.

-

Resistance Is Inevitable—and Usually Stronger Than Expected

Every empire imagines itself irresistible. Every empire is wrong.

From the Mapuche in Chile to the Vietnamese against France and the United States, from the Afghans against Britain, the Soviets, and the Americans, to the Algerians against France, resistance movements have repeatedly outlasted and outmaneuvered far stronger imperial forces.

The Philippines again offers a telling example. American commanders believed the war would last months. Instead, Filipino guerrillas fought for three years, forcing the U.S. to deploy 126,000 troops—an enormous force for the era—and to adopt increasingly brutal tactics to break the insurgency.

Resistance is not a bug in the imperial system; it is the system’s inevitable response. And it is almost always underestimated.

-

Atrocities Abroad Corrupt Democracy at Home

One of the most overlooked lessons of imperialism is the corrosive effect it has on the imperial nation itself. The violence required to maintain an empire does not stay overseas; it returns home in the form of militarism, racism, and authoritarianism.

Genocide scholars note that Western states not only committed atrocities abroad but later colluded with or facilitated genocides elsewhere—from Indonesia in the 1960s to Guatemala in the 1980s. The habits of empire—dehumanization, secrecy, impunity—become habits of governance.

The Philippine War again illustrates this dynamic. American soldiers wrote home describing torture techniques such as the “water cure,” a precursor to modern waterboarding. These practices, once normalized abroad, reappeared in later conflicts. The moral boundaries eroded by empire rarely rebuild themselves.

Imperialism is not simply a foreign policy; it is a domestic contagion.

-

Empires Create the Conditions for Future Genocides

Imperialism does not merely commit atrocities; it lays the groundwork for future ones. By redrawing borders, empowering certain groups over others, and imposing extractive political systems, empires leave behind fractured societies primed for violence.

As genocide scholars argue, the international order shaped by imperial powers has enabled postcolonial states to commit genocide—from Bangladesh in the 1970s to Rwanda in the 1990s. The imperial legacy is not just historical; it is ongoing.

The Belgian Congo is perhaps the most infamous example. King Leopold II’s personal empire killed an estimated 10 million Congolese through forced labor, starvation, and mutilation. When Belgium finally annexed the territory, it left behind a traumatized, destabilized society. The Congo’s post-independence history—dictatorship, civil war, mass killing—cannot be understood apart from the imperial violence that preceded it.

Empires do not simply fall; they explode.

-

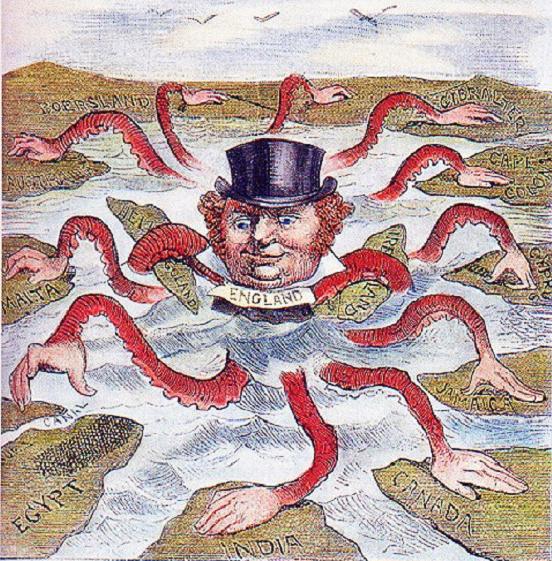

The World Eventually Turns Against Empire

Imperialism once carried the sheen of inevitability. Today it carries the stench of illegitimacy. The 20th century witnessed a global moral revolution: the rise of anti-colonial movements, the spread of human rights norms, and the creation of international institutions that—however imperfectly—challenge the logic of conquest.

The United Nations Charter explicitly prohibits territorial acquisition by force. Genocide conventions emerged in part because imperial atrocities forced the world to confront the scale of human destruction wrought by empire. Even the most powerful states now cloak their interventions in the language of liberation, democracy, or humanitarianism—an implicit admission that imperialism has become indefensible.

This shift is not merely rhetorical. It reflects a deeper recognition: empire is incompatible with the modern world’s moral and political expectations.

HWC925

-

Imperialism Always Ends in Failure—Even for the Victors

The final and most important lesson is also the simplest: imperialism does not work. It never has.

Spain’s empire collapsed under the weight of debt and rebellion. Britain’s dissolved after two world wars. France’s ended in humiliation in Indochina and Algeria. Japan’s empire evaporated in the ashes of 1945. The Soviet Union’s collapse was accelerated by its disastrous war in Afghanistan. The United States’ imperial ventures—from the Philippines to Vietnam to Iraq—have produced quagmires, not stability. Why should we believe Venezuela will be any different?

Imperialism is not merely immoral; it is unsustainable.

Conclusion: The Lessons We Keep Forgetting

The seven lessons of imperialism are not obscure. They are written in archives, in testimonies, in demographic collapses, in the ruins of burned villages, and in the memories of survivors. They are written in the statistics of democide—hundreds of thousands killed in the Philippines alone, millions more across Africa, Asia, and the Americas. They are written in the scholarship that links imperialism to genocide, repression, and mass atrocity across continents and centuries.

And yet, the temptation of empire persists. Great Powers still imagine that force can reshape the world to their liking. They still believe that conquest can be clean, that domination can be benevolent, that history can be defied.

But history is patient. And its verdict is clear.

Imperialism always fails.

The only question is how many lives will be lost before the lesson is learned again.