Between 1967 and 1970, an estimated 2 million Igbo Nigerians were killed by the Nigerian military after seceding to form the Republic of Biafra. After the failure of military attacks on the region known as Biafra, a military blockade induced famine and the Biafra Genocide. The Nigerian military added to the famine by bombing Biafra’s farms and agricultural supplies. The Biafra genocide was a deliberate attempt to starve the secessionist state into submission.

The end of World War II brought the collapse of the colonial system, which allowed European powers to dominate much of the world. The retreat of imperialism, however, did not equate to freedom and prosperity in the lands they left behind. In many, if not most, instances, the European powers managed their rule over colonized lands like Nigeria by establishing divisive political systems and structures. These constructs fostered extreme dysfunction and inequities in the new nations that claimed their independence in the post-World War II period. These dysfunctions often overlaid on already divided states artificially formed by the Europeans when they consolidated numerous ethnic groups and regions full of natural resources to their own interests – then called it a nation.

-

Also, check out: The Making of Nigeria, History of Africa Podcast Series Part 14

Nigeria boasts a whopping 250 ethnic groups. The three largest include the Hausa-Fulani (29%), Yoruba (21%), and the Igbo (18%). When Britain ruled over Nigeria as a colonial power, many of the various ethnic groups began migrating across the regions now consolidated to become Nigeria.

The Igbo became the most effective at integrating and benefitting from British rule. Compared to the other Nigerian ethnic groups, the Igbo more aggressively pursued western religion, education and spread throughout Nigeria with these advantages to seek employment and establish livelihoods after Nigeria declared independence in 1960. Although the Igbo hailed from the eastern part of the country, the Igbo had established lives throughout the country by the time of independence.

The 1964 national elections in Nigeria proved particularly violent and chaotic. The victories and overwhelming influence of individuals related to the northern part of the country appeared to many the result of corruption and fraud.

In 1965 a coup followed by a countercoup further escalated tensions and dangers in Nigeria. Many leaders in the military and government killed during the coup hailed from the northern part of the country, leading some Nigerians to mistakenly assume that the Igbo brought about the coup. In July 1966, northern soldiers initiated a counter-coup, installing Lieutenant Colonel Yakubu Gowon as the Supreme Commander of Nigerian forces.

From June to October 1966, a pogrom broke out in the northern part of Nigeria targeting Igbo. As many as 30,000 people died in the violence. Nearly half the victims were children. The massacres peaked on Black Thursday, September 29, 1966. On top of the violence, 1 to 2 million Igbo civilians fled to Nigeria’s eastern region.

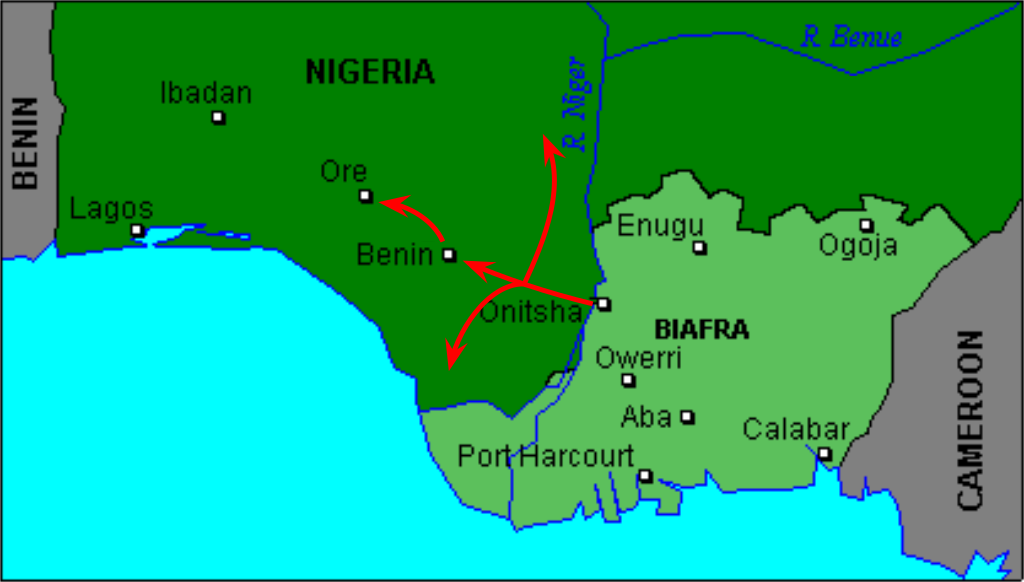

In May 1967, Gowon declared a division of Nigeria into twelve states. The Igbo, concentrated now mainly in the East Central State, found themselves cut off from Nigeria’s oil wealth. As a result, three days later, Colonel Odumegwu Ojukwu, the acting military governor of the eastern state, declared the independence of the Republic of Biafra. The declaration was as much to protect Igbo wealth in the east as it was to protect the masses of Igbo people fleeing to the east.

Only five other African nations recognized Biafra. Most of the world was more concerned about the status of Nigeria’s oil resources in the chaos of civil war that now engulfed the country. The US was distracted by Vietnam and much of the world grew concerned about global oil supplies in the shadow of the Six Days War during the same period. The British backed Nigeria with a heavy inflow of weaponry. Mercenaries massed to both sides of the fighting. From the summer of 1967 to 1969, Nigeria’s army grew from 7,000 men to 200,000 while Biafra’s grew from less than 300 soldiers to nearly 90,000.

Ojukwu blamed mounting Biafran military losses on saboteurs that infiltrated his army. He justified purges of Biafra’s military on that basis and destroyed the morale of Biafra’s military. Tensions also arose between the Igbo in Biafra and ethnic minorities. Rather than forming an alliance of defense against the Nigerian army, the Biafran military frequently carried out massacres against these ethnic minorities. The Nigerian army was doing the same thing, thereby placing ethnic minorities in an impossible situation where they faced threats on all fronts.

Beginning in 1968, the civil war fell into a stalemate. Nigeria’s military could not make further gains against entrenched Biafran forces. Ojukwu felt Biafra only needed to defend itself, and world sympathy would drive Nigeria back. It was in that stalemate that the greater tragedy of the Biafra genocide emerged.

The Biafra Genocide

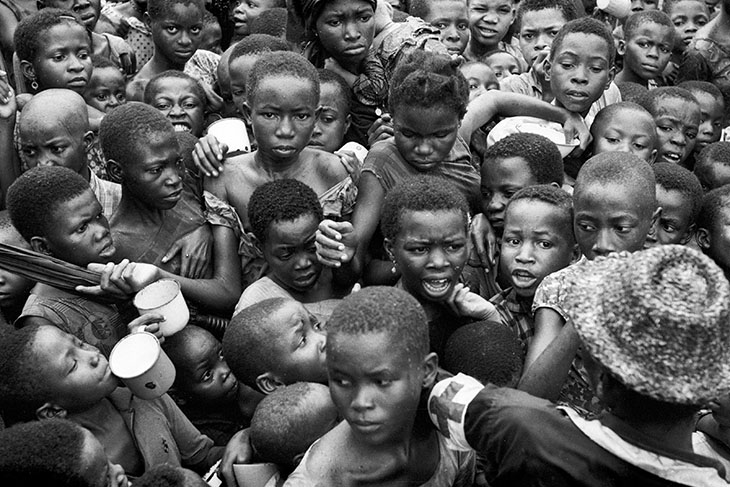

Nigerian forces set a strategic blockade around Biafra to starve the secessionists out in a siege-like atmosphere. Massive starvation fell upon the Igbo civilians in Biafra. The word “genocide” began to be used in the western media as the world was alerted that the Nigerian military was trying to starve to death 2 million people, half of them children.

In a strange twist, Igbo propagandists recruited public relations firms in New York and Geneva to garner world sympathy for their plight. That effort resulted in the ridiculous claim that Biafra represented the world’s first black-on-black genocide. It also created the popular image of post-war Africa as warring, corrupt, and poverty-stricken, with starving African children becoming the icon that many in the western world have associated with Africa ever since.

The civil war officially ended January 15, 1970, and the government declared “no victor, no vanquished.” Survivors saw that official statement and policy toward the genocide as denial and refusal to remember that it ever occurred.

Click on these links for more information on the Biafra Genocide: