In my 2019 book How the World Ends, I laid out three central crises: food, water, and population, that would serve as the foundation for a convergence of crises and chaos over the next half-century. The repercussions of these crises would compound. We are witnessing that today. This series of articles will track the continuing collapse of these essential systems in 2021.

When I wrote How the World Ends, I noted near the end of the book that new, “surprise events” like pandemics and terror attacks would accelerate the approach of the end of the world as we know it. The original design of the book included a section devoted to forecasting some of those events. In the end, I opted to turn those into podcast series, which you can find on the website. I reasoned there was only so much gloom one book could afford to present to a reader.

Today, less than 18 months since the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, we are beginning to see its effects on the global food system. Many hope that vaccines will stop the spread of the coronavirus, and indeed it may, but we are only in the beginning phases of the crisis that started in 2020. The period of globalization, which began in the 1980s and accelerated in the 1990s, fostered an intricate system where no nation exists on its own. The chaos in one part of the earth presents unintended consequences in another part of the planet. The pandemic significantly escalated crisis in the most strained parts of the world, and that crisis is spreading.

These growing trends of chaos are often presented within the narrative of climate change in the popular media. That is only part of the story. Understanding the increasing chaos today as the effects of climate change alone blinds us to the broader context and more immediate dangers unfolding before our very eyes.

In the early stages of the US experience with the pandemic, I masked up, gloved up, and held my breath as I went to the local grocery store for my family. The aisles were nearly abandoned. Everyone was afraid to go out in public. The more significant concern to me, however, was the price of ground beef. The usually well-stocked shelves of meat in the freezer section of the store were bare. Nasty remnants of extremely low-grade ground beef were strewn carelessly on a lower shelf, and its price was nearly four times what I typically paid for good ground beef. America’s supply chain was interrupted along multiple links, and this was only one area where it could be realized in our daily life.

The inquiry into the price, quality and supply of ground beef became my weekly barometer to measure how the country was faring in the pandemic. When the beef counters became stocked again, and the prices returned to normal, life was getting back to normal – or at least the new normal.

That new normal is not as benign as we might believe. The new normal includes higher prices and increasingly inept governments who cannot stop the pain from reaching their constituents.

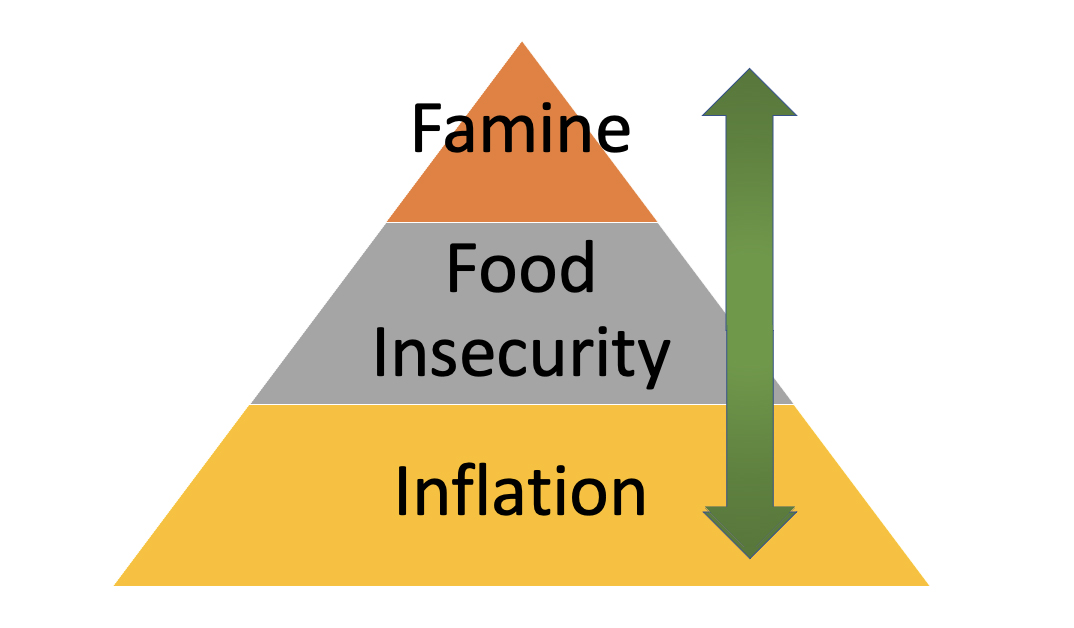

Levels of Food Crisis

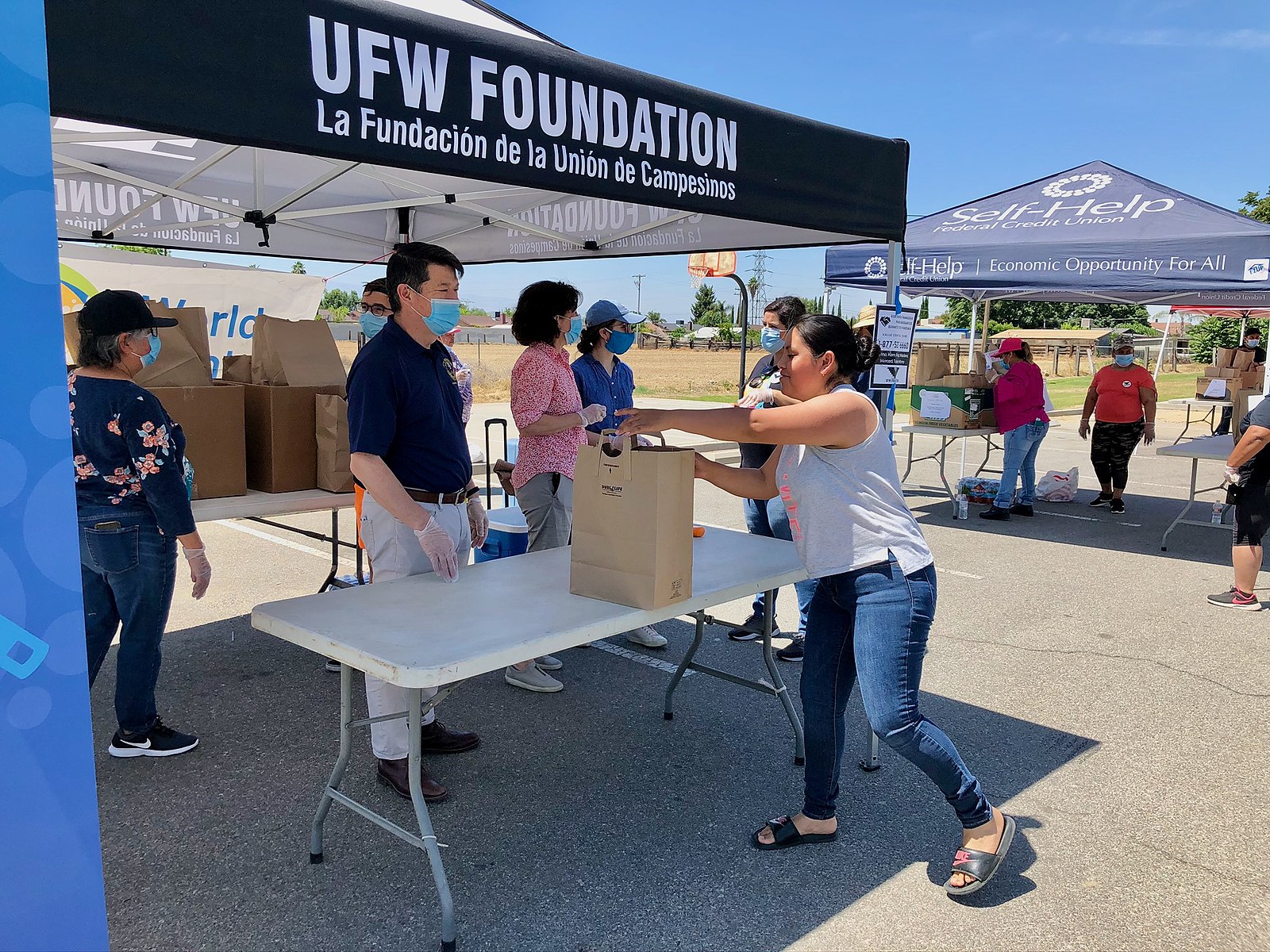

World hunger has been on the rise since 2016, but it experienced a terrible surge in the last year. According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, global hunger increased by 118 million people in the last year, the highest increase since 2006. There are levels to that crisis.

Starvation and Famine

Level one includes famine and the starving. Nations like the US and Great Britain have small populations that fit into this category, but in other parts of the world, vast segments of nations and even regions of continents are slipping into famine and starvation.

Earlier this month, the humanitarian organization Oxfam released alarming statistics that measured the state of the food crisis after one year of the pandemic. Every minute, eleven people on the planet die of hunger. The number of people experiencing famine-like conditions globally has increased by six times in the past year.

Areas where corruption, inequality, and suffering have finally boiled over into war experience the worst aspect of the food crisis. In those areas where distribution and supply lines are severed, the food crisis has perpetuated beyond any semblance of control. In mid-June 2021, the number of people falling into the most acute phase of the famine stood at 521,814 across Ethiopia, Madagascar, South Sudan, and Yemen – up from 84,500 last year, an increase of more than 500 percent, according to the global report on Food Crises 2021.

Food Insecure

The next level of the global food crisis is food insecurity. Food insecurity precedes famine when situations such as warfare or natural disaster prevent large populations from accessing food supplies.

A July report from Oxfam states 155 million people worldwide now live at crisis levels of food insecurity or worse – some 20 million more than last year. About two-thirds of them face hunger because their country is in military conflict. In the 55 food-crisis countries under review, almost 16 million children under age five were acutely malnourished, while 75.2 million children under age five experienced stunted growth.

Food Price Inflation

Finally, the third entry-level to the food crisis include those nations experiencing food price inflation. Areas of the planet experiencing this level of the global food crisis do not have an issue of supply. They have an issue of price. The price of food is increasing. Hardly any nation on the planet is exempt from this reality today.

According to a report from the Economic Research Service and Department of Agriculture, US food prices were expected to increase 3.5% year to year in 2021. Those expectations were built upon assumptions that the pandemic would be brought under control and the country could begin to normalize. An assumption that is not guaranteed! In fact, that assumption may already be proving unreliable as a more recent report said US inflation leaped by 5% in the last year, the highest jump in 13 years. In the US situation, price increases take the greatest impact on the poor. Food price inflation means the poor, to escape the pressures of inflation, can still purchase cheaper and lower quality foods but will suffer poorer health as a result. That is a troubling scenario in the US, but not a crisis.

In some places, food prices are jumping so high that it is pushing national populations into the level of food insecurity. The World Food Program recently issued alerts that wheat flour prices in Lebanon rose 219% year-on-year, cooking oil prices soared 440 % versus a year ago in Syria. World food prices rose 33.9% year-on-year in June, according to the UN food agency’s price index, which measures a basket of cereals, oilseeds, dairy products, meat, and sugar. The UN Food Agency said the global food price index grew by its highest level since 2011.

As a result of statistics like these worldwide, food insecurity increased by 40% compared to a year ago. In other words, more people moved into the more dangerous level of the global food crisis compared to a year before.

This Is Not Momentary

Although political leaders would like to believe otherwise, these shifts are not momentary periods of crisis. When it comes to basic needs like food supply, people do not wait for the crisis to pass and situations to improve, particularly when they have lost faith in their governments to competently govern through the crisis. Foundational crises revolving around food spread and morph into more complex issues such as extremism, political unrest, and even war.

Understanding that dynamic changes how we perceive what is unfolding in Cuba, South Africa, and elsewhere in recent weeks.

In Nigeria, inflation has hit 18% in the last two months. Food prices have increased more than 22% since the start of the pandemic. The World Bank estimates that inflation and rising food prices pushed another 7 million Nigerians into poverty during that period.

As a result, in Nigeria, bandits are applying the methods first employed by the Islamic terrorist group Boko Haram, kidnapping more than 1,000 Nigerian students for ransom since December. Militias have taken over major farmlands and key agriculture transport corridors.

That pattern is duplicating across many areas of the world where the food crisis is stressing individuals and groups fed up with corrupt or incompetent governments. They are taking matters into their own hands. The actions of frustrated extremists never resolve the crisis in the long run. They make the situation worse, driving their nations up the ranks of the levels of food crisis.

What to Watch

As the crisis escalates, we can watch situations to maintain alertness and better understand what is unfolding.

Pay careful attention to natural disasters and political events that could push a nation from one level of food crisis to the next. Nations like Venezuela, Peru, Nigeria, and others could be pushed over to the line into the next level of food crisis by events that may otherwise seem unrelated. The world aid system is already strained due to the pandemic, and the global safety net the world has relied on for more than half a century cannot function like it once did.

Also, give attention to the potential spread of the crisis. Nations no longer exist in isolation, and neither does their chaos. The escalation in the causes chaos in one area quickly effects chaos in another part of the world. It is no coincidence that growing food chaos, violence, and political upheaval since 2016 can be tracked across a geographic belt stretching from the Sahel of Africa to Yemen in the Middle East. Crisis spreads and grows in our current environment.

When these crises occur, beware of misguided narratives among the media and political leaders that seek to explain what is happening. The western world is often too quick to interpret everything through the lens of democratic rights and individual freedom. In the strained state of the globe today, Maslow’s hierarchy needs is a better guide to interpreting the chaos than the writings of Thomas Jefferson.

Additional Reading on the Food Crisis

- The Whole World Eats Well, We Do Not (Washington Post)