This post on the water crisis in Iran is part of the ongoing series where we are tracking the global water crisis.

Claudia Sadoff, a water expert who prepared a report for the World Bank recently explained how in Iran, “25 percent of the total water that is withdrawn from aquifers, rivers, and lakes exceeds the amount that can be replenished.” Within the next 50 years, the aquifers that fuel almost half of Iran’s provinces will be entirely depleted. Lakes are shrinking as dams have been constructed to divert water to the cities. Lake Urmia which was once one of the largest saltwater lakes in the region has shrunk by 90 percent since the 1970s.

In 2013 the former head of Iran’s environmental protection agency asserted that 85% of the country’s groundwater is gone.

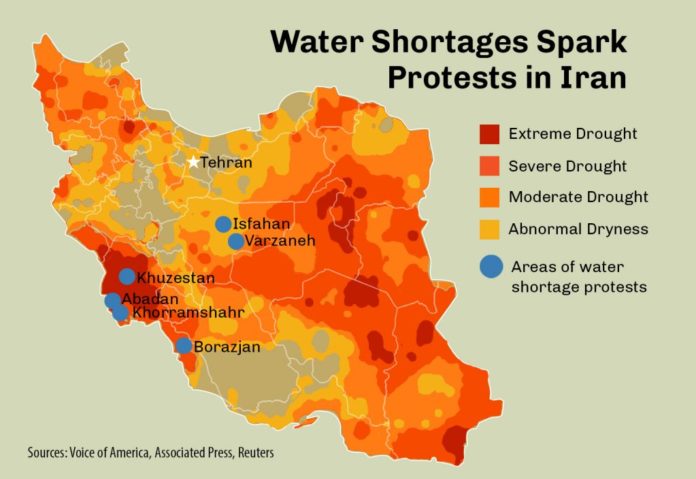

According to a report from the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, in 2017 Iran’s precipitation levels decreased by 25%. This, in turn, resulted in a 33% reduction in Iran’s reservoirs and dams by 2018.

In Iran, 92% of its renewable water goes to the agricultural sector. In most countries, this number is around 70%.

Protests in recent years have been seen much more rooted in water scarcity issues than politics or desires for democracy. Farmers are being forced to cut back on water usage and many see the distribution of the nation’s water to be something often infested with cronyism. Tehran alone, the capital of Iran, consumes 20% of the nation’s drinking water.

Changing weather patterns and climate change can be cited as part of the cause of Iran’s water shortages. More significant than either of these however is simple incompetence, corruption, and mismanagement among Iran’s leaders. A recent article in Foreign Policy asserts that Iran’s leaders are committing national suicide by dehydration.

After the 1979 Islamic Revolution, the new government of Iran was assertive in reforming the nation’s irrigation system. Hundreds of new dams were built along with new networks of water transfers and pipelines. Construction companies closely aligned with Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Corps benefitted from this major infrastructure project but it was all a waste. The new waterworks actually prevents water from reaching many parts of the country. As a result, aquifers were further drilled into and depleted.

The number of wells in the country (digging into the nation’s shrinking aquifers) increased from 60,000 to 80,000 since the Islamic Revolution of 1979.

When we see unrest and upheaval in Iran we frequently consider it within the context of politics and American foreign policy. This is usually inaccurate. The growing frustrations in Iran are about people being thirsty and an agriculture system beginning to collapse.

This is the same story being repeated in many other parts of the world, all part of the global water crisis.

[…] Oil. Wealth. None of these have shaken Khuzestan province like the Iranian water crisis is about to. Iran is consuming more water than it can replenish. In the next 50 years, the aquifers […]

Comments are closed.